EN - Introduction to Hacking Android

This article might help you to reverse Android application and access new features upon it. I disclaim any liability if you use this article for illegal actions.

Thanks @cyxo_o for helping me on this

Live presentation on Twitch

H25 is a startup founded by @clement_hammel & @MathisHammel - code contests, CTF, and lots of streams. Join them on http://discord.h25.io and http://twitch.h25.io

Explanations

Let’s take the case of a known temporary mail service TempMail (https://temp-mail.org/). While the service has provided completely free access to its API for years, restrictions on its use have had to be put in place to avoid recurring abuse.

Android application analysis

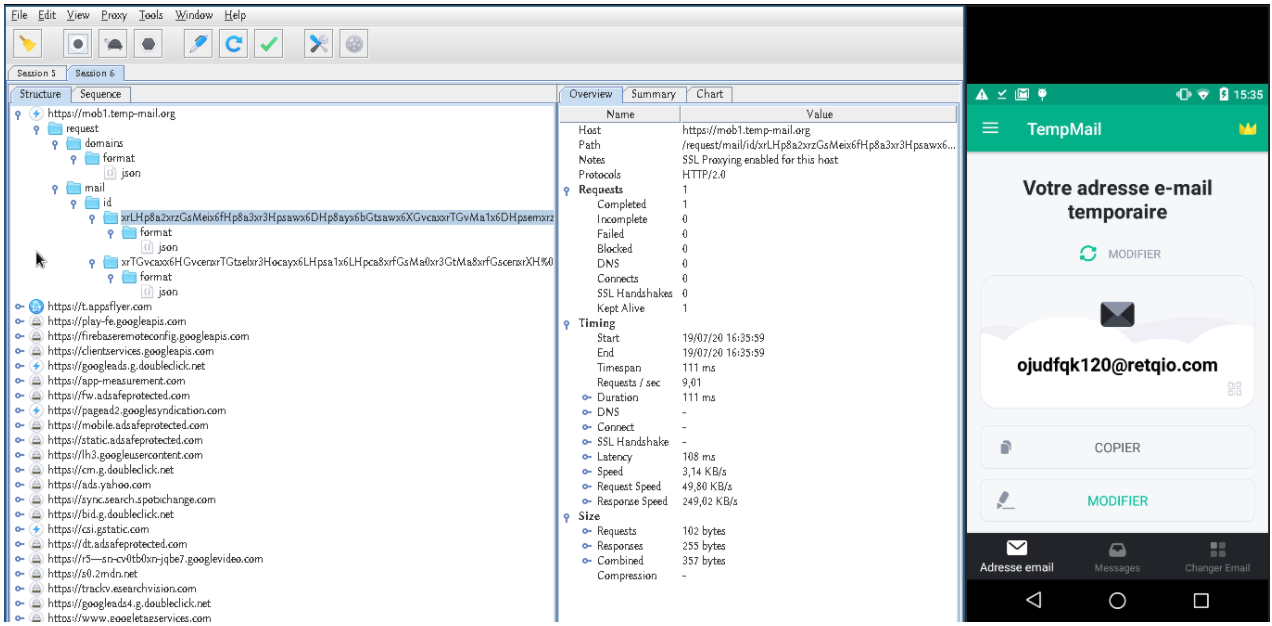

Let’s analyze network traffic:

After installing the APK on an Android, let’s use Charles Web Debugging Proxy, a cross-platform HTTP debugging proxy server application written in Java. It allows the user to view HTTP, HTTPS, HTTP/2 and TCP port enabled traffic accessible from, to or through the local computer. The mobile phone is controlled on the computer using scrcpy, to facilitate the visualization of the requests according to the actions on the telephone.

We notice that a very little network flow leaves the application to the https://mob1.temp-mail.org server, and we notice that only two endpoints are used:

1) /request/domains/format/json allows you to retrieve the list of domains from which email addresses are generated:

$ curl https://mob1.temp-mail.org/request/domains/format/json

["@mailer2.net","@mailivw.com","@qlenw.com","@retqio.com","@romails.net","@royalnt.net","@tmauv.com"]

2) /request/mail/id/<id>/format/json allows you to obtain the content of received mails corresponding to the address displayed on the application:

$ curl https://mob1.temp-mail.org/request/mail/id/xrPGt8azxrPHosehxrHHosa8xrXGt8a3xrfGssehx6bHocazx6DGvcehx6DGsca3x6bHosa8x6LG%0Atsa3xrTHoA==%0A/format/json

{"error":"There are no emails yet"}

Since the change of addresses does not involve any network traffic, we understand that they are generated randomly on the client side and that the application retrieve the content of emails. We are therefore faced with the following problem:

How is the payload corresponding to the <id> generated in the GET request made to the server ?

It should be noted that in most web services offering applications, application/API exchanges are sufficient to carry out abuses (LeCab, LeBonCoin, etc.)

Reverse of the application

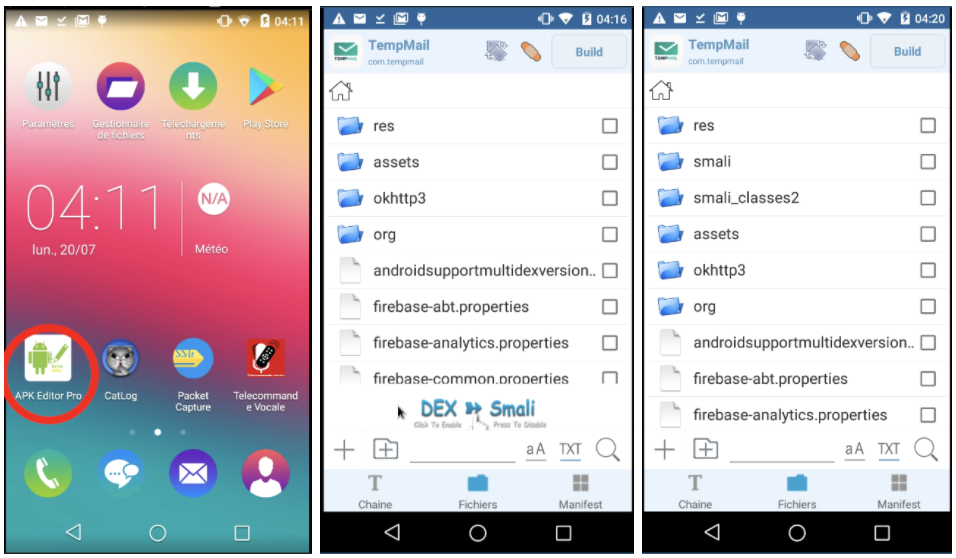

First, we analyzed the application from our mobile phone using the APK Editor Pro application.

- Select the TempMail APK (com.tempmail) from the applications

- Select “Complete Edition” (RE-COMPILE)

- Files tab, DEX button → Smali

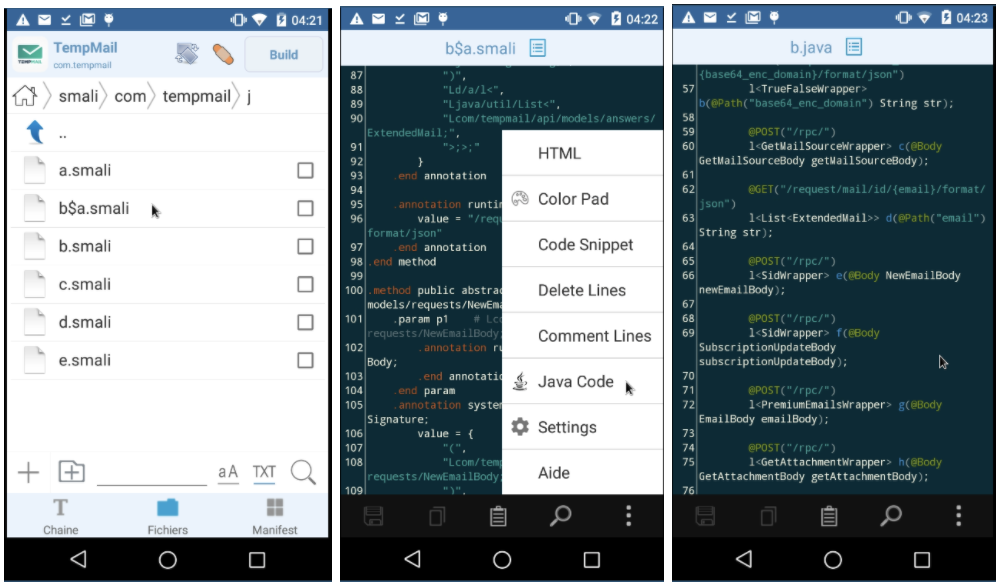

- A smali folder appears that we will explore, we can select the files in .smali and convert to java for a better understanding

Secondly, we chose to work from our respective computers to be able to more easily copy the extracted java code and use it to verify that the payload built corresponds to what we were looking for. We extract the application on the computer using ADB:

$ adb shell

shell@L5251:/ $ su

root@L5251:/ # cp /data/app/com.tempmail-1/base.apk /mnt/sdcard/

root@L5251:/ # exit

shell@L5251:/ $ exit

$ adb pull /mnt/sdcard/base.apk /tmp/base.apk

/mnt/sdcard/base.apk: 1 file pulled, 0 skipped. 3.3 MB/s (4941426 bytes in 1.443s)

We then used the JADX APK decompiler to grab the java files. Most of the exploration has been done using grep. Here is the exploration tree:

Source: https://github.com/zteeed/tempmail-apks/raw/master/2020-11-04-tempmail.apk

1) com/tempmail/l/b.java

/* compiled from: ApiClient */

public class b {

public interface a {

@GET("/request/mail/id/{email}/format/json")

l<List<ExtendedMail>> d(@Path("email") String str);

}

}

We are therefore looking for occurrences of l.b.a

2) com/tempmail/services/CheckNewEmailService.java

public void g(String str) {

this.f13024e.b((d.a.y.b) com.tempmail.l.b.a(this).e(x.k(str)).subscribeOn(d.a.e0.a.b()).observeOn(d.a.x.b.a.a()).subscribeWith(new b(this, str)));

}

The e attribute of l.b.a(this) is well used, which corresponds to the function taking as argument what one can assume to be the strange id in base64. And it’s x.k(str) that is passed as an argument.

3) com/tempmail/utils/x.java

public class w {

public static String l(String str) {

try {

byte[] digest = MessageDigest.getInstance("MD5").digest(str.getBytes());

StringBuilder sb = new StringBuilder();

for (byte b2 : digest) {

sb.append(Integer.toHexString((b2 & 255) | 256).substring(1, 3));

}

return sb.toString();

} catch (NoSuchAlgorithmException e2) {

e2.printStackTrace();

return "";

}

}

public static String k(String str) {

Integer num;

String l = l(str);

m.b(f13134a, "xor key 1573252");

try {

num = Integer.valueOf("1573252");

} catch (NumberFormatException e2) {

e2.printStackTrace();

num = null;

}

if (num != null) {

l = v.b(l, num.intValue());

}

String str2 = f13134a;

m.b(str2, "encodedString " + l);

return l;

}

}

We understand that an operation is performed between the MD5 of the mail and 1573252 at the level of a v.b function and that the result of this function constitutes our payload.

4) com/tempmail/utils/v.java

/* compiled from: StringXORer */

public class v {

private static String a(byte[] bArr) {

return Base64.encodeToString(bArr, 0);

}

public static String b(String str, int i) {

String c2 = c(str, i);

String str2 = x.f13134a;

m.b(str2, "xor " + c2);

return a(c2.getBytes());

}

private static String c(String str, int i) {

StringBuilder sb = new StringBuilder();

for (int i2 = 0; i2 < str.length(); i2++) {

sb.append((char) (str.charAt(i2) ^ i));

}

return sb.toString();

}

}

Our payload is therefore the base64 of the xor between each character of the md5 of the mail and the number 1573252.

However, this does not a priori explain the presence of URL-encoded carriage returns in the base64 payload %0A. By analyzing the network exchanges again, we realize that these carriage returns are systematically placed after the 76th character of the base64 and another at the end. We’re trying to rebuild the payload from the email to see if it’s working.

Proof of concept

JAVA

import java.util.*; import java.lang.*; import java.io.*; import java.security.MessageDigest; import java.security.NoSuchAlgorithmException;

public class Main

{

public static void main (String[] args) throws java.lang.Exception

{

String mail = "vkgwbld593@royalnt.net";

String s = make_payload(mail);

String payload = s.substring(0,76) + "%0A" + s.substring(76, s.length()) + "%0A";

String result = mail + " --> " + "https://mob1.temp-mail.org/request/mail/id/" + payload + "/format/json";

System.out.println(result);

}

public static String md5(String str) {

try {

byte[] digest = MessageDigest.getInstance("MD5").digest(str.getBytes());

StringBuilder sb = new StringBuilder();

for (byte b2 : digest) { sb.append(Integer.toHexString((b2 & 255) | 256).substring(1, 3));}

return sb.toString();

} catch (NoSuchAlgorithmException e2) {

e2.printStackTrace(); return "";

}

}

public static String make_payload(String mail) {

String mail_md5 = md5(mail); int i = 1573252;

StringBuilder sb = new StringBuilder();

for (int i2 = 0; i2 < mail_md5.length(); i2++) {

sb.append((char) (mail_md5.charAt(i2) ^ i));

}

return Base64.getEncoder().encodeToString(sb.toString().getBytes());

}

}

PYTHON

import base64, hashlib, json, requests, random, string

base_url = 'https://mob1.temp-mail.org'

headers = {

"authority": "mob1.temp-mail.org",

"accept": "application/json",

"accept-encoding": "gzip",

"user-agent": "okhttp/3.14.7"

}

domains = json.loads(requests.get(base_url + '/request/domains/format/json', headers=headers).content)

email = ''.join(random.choice(string.ascii_lowercase) for i in range(7)) \

+ ''.join(random.choice(string.digits) for i in range(3)) \

+ random.choice(domains)

input(email + '\n') # Send an email and wait a couple of seconds...

md5 = hashlib.md5(email.encode()).hexdigest()

xor = ''.join([chr(((ord(char) ^ 1573252) % (2**16))) for char in md5])

b64 = base64.b64encode(xor.encode()).decode()

payload = b64[:76] + "%0A" + b64[76:] + "%0A"

r = requests.get(base_url + f'/request/mail/id/{payload}/format/json', headers=headers)

print(json.dumps(json.loads(r.content)))

What protections?

SSL pinning is a mechanism that can be used to improve the security of a service or site that relies on SSL certificates. It allows you to specify a cryptographic identity that must be accepted by users. The certificate fingerprints are stored on the mobile application, for example, which prevents the use of SSL proxies to study the traffic sent between the mobile phone and the API. This does not of course prevent them from being replaced in the application by those from the SSL proxy and then recompiled.

In addition, obfuscation work can make the reverse engineering task more difficult even if it does not prevent the reverse of the application itself. As we have seen here, obfuscation in Java is quite limited because the classes of the different libraries of the JVM or of the Android library cannot be renamed and appear clearly on decompilation.